This article originally appeared on WRI Insights here.

The dense forests of Guatemala seem to go on forever. After all, the country’s name means “the place of many trees” in the Nahuatl language. Forests cover 33% of its land, and Guatemala is home to the world-famous Maya Biosphere Reserve, where Indigenous communities protect and sustainably manage about 450,000 hectares (111,000 acres) of forest ecosystems.

But outside of those community-managed protected areas, the forest is suffering. Because of the wealth of its soil and natural resources, and the expansion of agriculture, millions of people looking to make a decent living have exhausted the country’s land and cut down more than 18,000 hectares (44,000 acres) of its forests annually.

Even so, farmers are seeing lower and lower yields of the staple crops, like corn, that they grow to eat and sell on the market — 47% of the population now suffer from chronic malnutrition as they struggle to access enough food.

Mártir Gabriel Vásquez Us has made protecting and restoring the country’s trees his life’s work. As the Deputy Manager of Guatemala’s National Forest Institute (INAB), he and his fellow policymakers are now helping local landholders and Indigenous communities improve local incomes and food security, safeguard rare plants and animals, and store planet-warming carbon.

How? By paying them to plant and maintain millions of trees in damaged or at-risk areas.

Paying people to grow trees and protect forests sounds simple, but the Guatemalan government’s PROBOSQUE program is a sophisticated way to reward farmers and forest dwellers for the valuable ecosystem services — like clean water and healthy soil — that underpin the country’s economy and rural livelihoods.

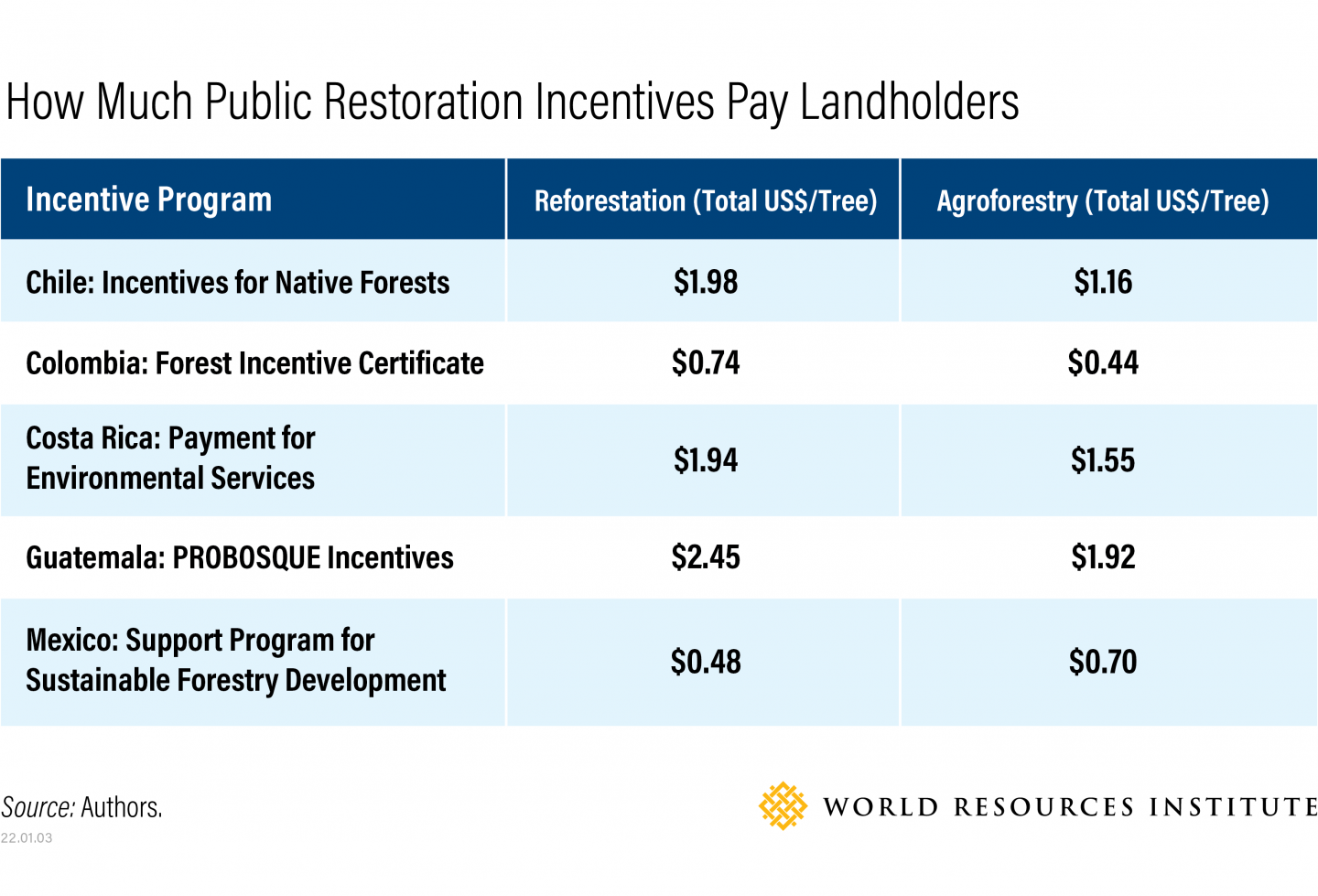

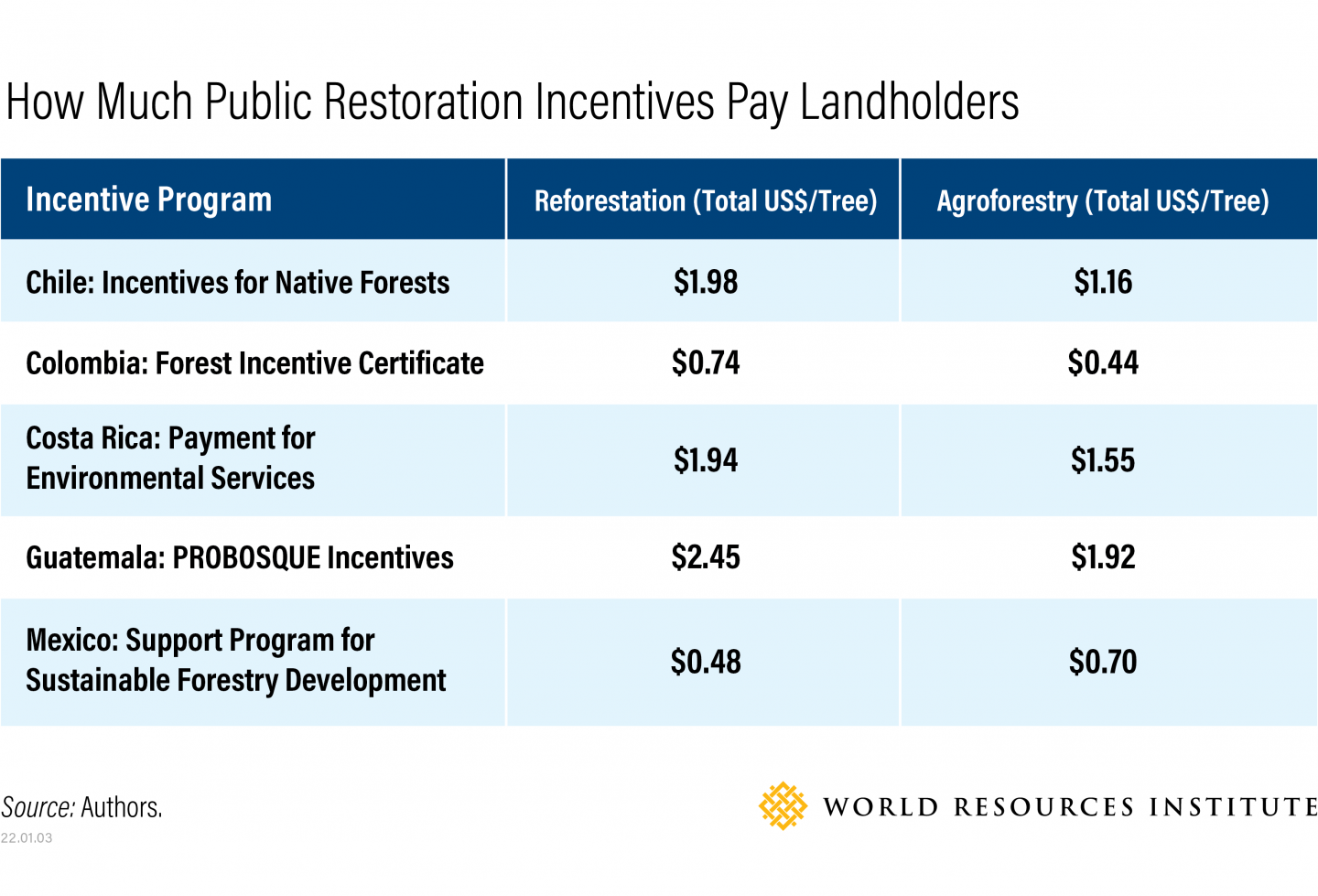

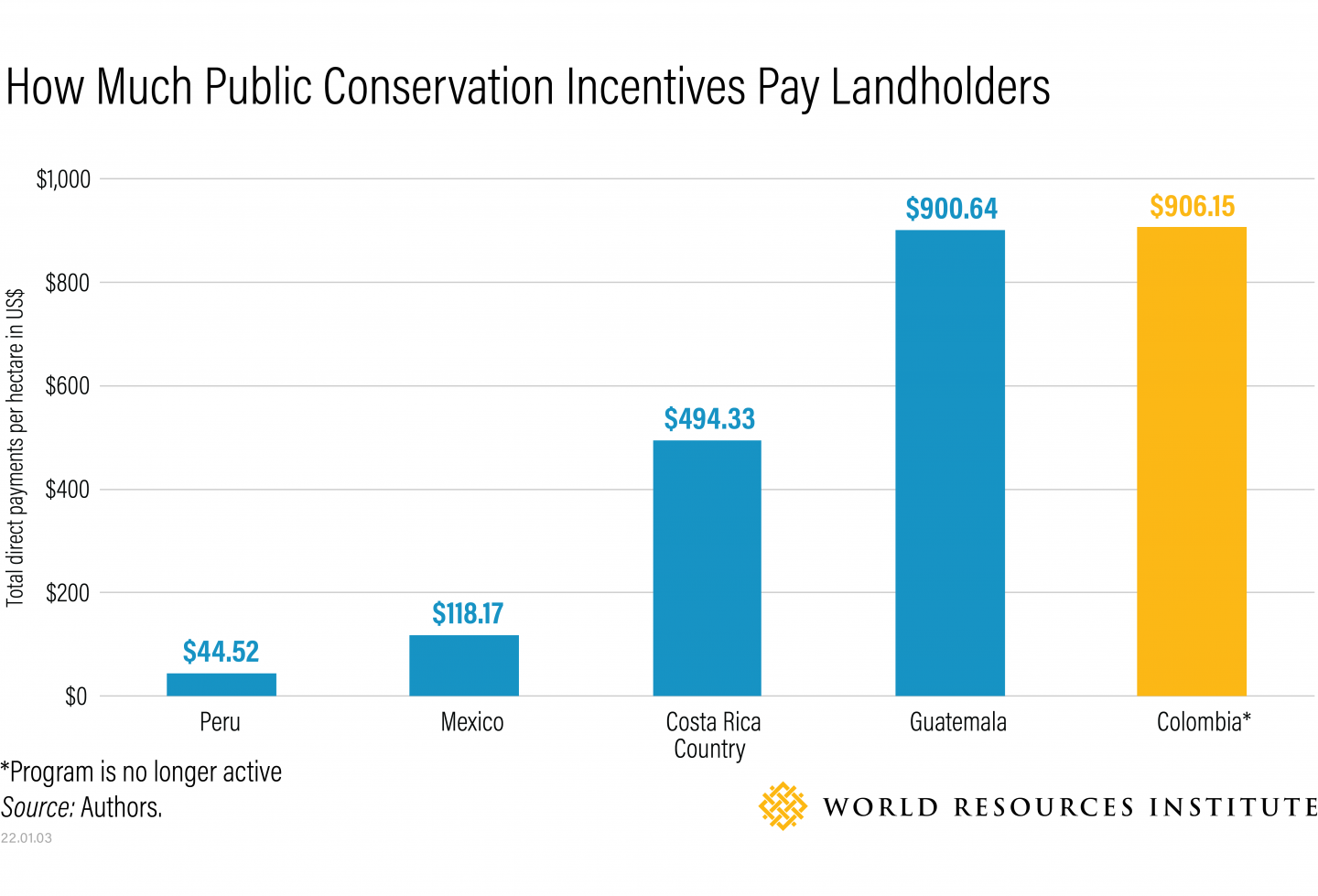

Vásquez and his fellow policymakers know that poverty can prevent rural landholders from making land use decisions that benefit the environment. PROBOSQUE has given them a nudge, paying $2.45 per tree to reforest the land and $1.92 per tree that they grow along and within their farms in agroforestry systems. Farmers are also encouraged to protect the remaining trees on their land; for every hectare of forest conserved, the government pays around $900.

“The PROBOSQUE incentives are about more than the hectares restored across the landscape. They are also about economic development and recovery and contribute directly to improving the livelihoods of Guatemala’s rural people.” — Mártir Gabriel Vásquez Us, deputy manager of Guatemala’s National Forest Institute.

The policy has had a major impact on more than 3% of the country’s total land: Since 1997, the government reports that landholders have begun to restore more than 135,000 hectares (333,500 acres) of land, and have conserved 200,000 hectares (494,000 acres) of land and sustainably managed 4,000 hectares (9,800 acres) of natural forest.

Decades of Experience Incentivizing People to Restore Land

Guatemala isn’t alone in its quest to use the power of public resources to restore land. A WRI issue brief evaluated the policies of six countries across Latin America — Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Mexico and Peru — that help landholders protect and restore trees across the landscape.

To better understand how these innovative policies work, the brief’s authors calculated the total payment that a landholder receives for each tree they grow (or each hectare of forest they protect) within each program.

This first-of-its-kind practical analysis allows policymakers to compare the total cost of each program across countries, ranging from $0.48 to $2.45 per tree for reforestation, $0.70 to $1.92 per tree for agroforestry, and $44 to $906 per hectare for conservation.

Because the programs provide consistent payments for five to ten years, they encourage landholders to plant and maintain their trees, while focusing government spending on the vulnerable years of a tree’s youth. When the trees are mature enough to survive without extra labor from the landholders, the payments stop, and the programs can then redirect the funding to help more farmers.

Toward Stronger Land Restoration Incentives

The INAB team knew that their program was helping people, but they also knew that they could more efficiently and effectively leverage the government’s precious revenue. When WRI and the Initiative 20x20 regional restoration alliance invited Guatemala to join the Restoration Policy Accelerator — a peer-to-peer learning program for policymakers looking to build strong, equitable public incentives for restoration — they jumped at the chance.

Since 2020, INAB has learned from the experiences of fellow policymakers from Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, Mexico and Peru and shared their own triumphs and challenges. At the same time, technical advisors have exposed them to the latest knowledge and insights from the global restoration community, ranging from how to build more equitable and inclusive programs for Indigenous peoples and women to how to better understand the complicated yet growing global carbon market.

How Governments Can Reward Farmers for Land and Forest Conservation Efforts

After studying the inner workings of dozens of policies and meeting with their creators and implementers, WRI identified seven recommendations that can help government leaders around the world craft the strongest and most equitable public incentives for restoration.

1. Prioritize the areas that could most benefit from restoration.

To maximize impact, policymakers should prioritize restoration techniques that create the most benefits for rural development, biodiversity, the climate and a myriad of ecosystem services. For example, incentives that encourage landholders to grow native trees alongside their commercial crops can improve biodiversity, sequester carbon and boost incomes — ensuring trees remain in the ground for the long run.

It’s important to note that each decision on how to use the land prioritizes some benefits over others. While embracing agroforestry may be a good decision for a cacao farmer looking to boost their yields, it won’t help a corn or bean farmer whose crops can’t tolerate shade.

2. Improve monitoring and transparency.

Currently, the only information that most governments publicly report is the number of hectares enrolled in each program, but that says little about ecological and economic impact. Independent and accurate progress-tracking systems — which combine the best high-quality, low-cost satellite data with field-collected insights — can show public and high-level decision-makers that investing in restoration is worth the up-front cost. Policymakers can use that data to highlight areas for improvements and grow their prominence on the international stage, too.

3. Create economic value for long-term sustainability.

Restoration won’t work unless it continues to pay landholders, long after the last payment leaves the bank. Creating sustainable and profitable value chains for products that are grown on newly restored land, like cacao and native fruits, can provide yet another source of income for farmers. As more countries begin tapping into the global carbon market, governments can provide additional income to farmers, especially when trees are young and not able to produce fruit or other products.

These sustainable value chains can protect the natural ecosystems that public incentives are rebuilding, even if incentive programs expire or run out. This is also important for private investors: If their projects can harness public incentives to cover some of their up-front costs, restoration becomes less risky and a more attractive economic opportunity.

4. Make it easier for all landholders to receive payments.

Landholders need easy access to incentive programs. By eliminating red tape and burdensome eligibility requirements for payments, governments can reach more people and help them restore more land. Policymakers need to communicate about their programs widely and consistently, with a special focus on reaching the women and Indigenous communities that past programs have sidestepped.

5. Emphasize the importance of native trees in land restoration.

Government incentive programs should reward landholders that use a mix of native tree species in restoration to maximize biodiversity, carbon storage and long-term climate resilience. They should combine the latest tools and research with local knowledge to help landholders grow the right species in the right places. And they should use their in-house research and development arms to help native trees grow better and more quickly, making them more competitive against the high-value, fast-growing exotic trees that many farmers prefer.

6. Attach programs to laws and robust institutions.

Many national programs, such as Sembrando Vida in Mexico, are originally created through executive orders from the office of the head-of-state. This means that if a program’s advocate leaves office, there is no guarantee that it will continue beyond the current administration. Policymakers should work with legislators to enshrine impactful programs into national or local laws to guarantee a program’s sustainability.

7. Align agriculture, forestry and finance sectors.

Governments often have dozens of public incentives that support agriculture, forestry and biodiversity. When policies conflict, they can cancel out each other’s effects.

For example, a program that pays farmers to expand cacao production, without any safeguards, could encourage landholders to cut down natural forests in order to expand the area of land they are cultivating. That goal could directly contradict a government’s climate commitment to end deforestation and restore natural forests.

National ministries of finance, agriculture, planning, economic development and environment must work together to harmonize their public policies and create programs that help produce crops and commodities sustainably.

Small Tweaks to Land Restoration Policies Lead to Big Rewards

We’ve highlighted these broad recommendations for policymakers, but how does the tricky process of implementing these reforms work in practice?

Back in 2020, INAB wanted to expand the number of Guatemalan landholders that had access to the PROBOSQUE payments but didn’t know how. Working with WRI, Vásquez and the team identified that their current monitoring system was burdensome.

To verify that the public incentive was leading to an improvement in tree cover, INAB staff had to visit remote communities and assess, in person, the progress of each landholder. Because site visits consume precious time, the staff could only reach 10,000 new beneficiaries per year.

By embracing the latest satellite monitoring techniques, which show where trees are located both inside and outside of dense forests at very high resolution, they could cut down on the number of site visits INAB staff would have to make each year. That would free up limited staff time to invite new landholders to join the program — and bring 10,000 more hectares (24,700 acres) per year under restoration, according to our estimates.

These lessons from Guatemala and elsewhere in Latin America have much to teach the world as the UN Decade on Ecosystem Restoration accelerates: Public subsidies can help fill the massive restoration gap and reward landholders for their role as ecosystem stewards.

By demonstrating that paying for land restoration can lead to positive environmental outcomes, governments can convince private investors that every dollar spent can have an outsized impact on people and the planet.

Most importantly, these examples show that the complicated process of policy reform isn’t impossible, and that more people can benefit from the life-changing work of landscape restoration when policymakers work collaboratively to find solutions.

The Restoration Policy Accelerator is expanding across Africa and India. Receive the latest updates directly in your inbox by signing up here.