Integrated landscape management in Latin America presents complex challenges, marked by structural inequalities that disproportionately affect vulnerable groups, especially women, youth and indigenous peoples. Throughout its more than 20 years of action, the Latin American Model Forest Network (RLABM) has learned that implementing a gender perspective is not only a matter of equity and justice, but a critical factor in achieving sustainability in its member landscapes.

Experience in various territories in the Latin American region has shown that the inclusion of women in the management, conservation and restoration of forests and ecosystems brings significant benefits that transcend the ethical and legal principles of equality. Women possess ancestral knowledge about the sustainable use of biodiversity, water management and other ecosystem services that are fundamental for community well-being and resilience to factors such as climate change. Women's equal participation in decision-making at the family, community and landscape levels allows for the incorporation of differentiated and integral perspectives to address structural and environmental inequalities, as well as being an indispensable condition for achieving equal opportunities and living in a just society.

Despite this, no territory or landscape in Latin America is immune to the problem of gender inequality. These situations are rooted in deep-rooted social and cultural structures, which in most cases start by assigning differentiated roles to men and women in practically all human spheres. Historically, women have been relegated to domestic care activities, which are unpaid and undervalued, generating an invisible work overload that extends beyond the family level and is reflected in collective spaces, even affecting the exercise of social and political life.

These situations are aggravated by various factors, one of the main ones being restricted access to economic resources such as land ownership, financial credit and other productive resources. This is reinforced by the absence of a policy framework that fully recognizes and addresses these problems, does not consider the needs and particularities of women in environmental management, and does not provide the necessary conditions to reverse these situations, sometimes aggravating them.

Moreover, gender violence, discrimination and still high and normalized, undermines women's self-confidence in governance processes, being an invisible and little addressed barrier that limits their public participation and reinforces their exclusion in the exercise of public office. This situation is even more critical when factors of ethnicity, geographic location and age are added, since the region still experiences "adultcentrism" and marginalization of indigenous peoples, which relegates young people, indigenous peoples and the population living in rural areas, making their voices and knowledge invisible.

This Blog details how the Latin American Model Forest Network has integrated a gender approach in its efforts to promote inclusive landscape governance, especially through three site-specific investigations developed in Model Forests in Peru and Guatemala.

Workshop with young people in the Pichanaki Model Forest

Model Forests: governance platforms towards gender equity

Model Forests (MFs) are territorial governance platforms that operate under six working principles, in order to foster collaboration among diverse actors to achieve sustainable development. The MFs are associated in networks, grouped at the global level by the International Model Forest Network, which associates regional networks such as the Latin American Model Forest Network (RLABM), the latter being made up of 34 territories in 15 countries.

In recent years, gender equity has become a key focus within RLABM. The formulation of the first Gender Strategy in 2017 marked a milestone in the incorporation of this approach in governance, establishing education, strengthening of social and political capital, and improvement of tools as main pillars. Since then, there have been tangible advances in the participation of women in the Network, with one of the most notable achievements being the creation of a Gender Commission and the growing presence of women on the RLABM Board of Directors, which has been reflected, for example, in the diversification of its work agenda. In addition, the training and working groups promoted by the Network have progressively achieved greater gender parity, reflecting a structural change towards inclusion. An emblematic example is the Latin American Model Forest Youth Network, whose recent formation has ensured the equal participation and representation of men and women since its inception.

Monitoring progress in the territories remains a challenge. A 2021 study characterized the most common strategies in model forests, such as training for women farmers and entrepreneurs, specialized financing and the creation of specialized productive infrastructure. However, there is still a need for further research on gender issues in territorial governance.

Case Studies

To better understand gender dynamics in landscape management, between 2023 and 2025, RLABM promoted qualitative research in the form of postgraduate theses of CATIE's Masters in Management and Conservation of Tropical Forests and Biodiversity, in three specific WBs:

- Apurímac-Abancay Model Forest (AMF), Peru: Nestled in the Peruvian Andes, this MF encompasses a mosaic of ecosystems including forests, wetlands and high Andean grasslands. Despite its natural beauty, it faces challenges such as forest fires and land degradation. Its governancemulti-stakeholder , centered in a subnational government agency, seeks to balance conservation, restoration and sustainable development for Quechua-speaking farming communities.

- Los Altos Model Forest (BMLA), Guatemala: Located in the Western Highlands of Guatemala, it extends through eight municipalities with a mostly Mayan population. Its ecological diversity favors the development of agriculture, forestry and artisanal production. However, deforestation and forest fragmentation remain key challenges, addressed through a Forest Roundtable for Region VI.

- Pichanaki Model Forest (BMPi), Peru: Located in the high jungle of the Peruvian Amazon, it is home to a diversity of ecosystems from the Yunga to the humid puna. Agriculture is its main economic activity, with crops such as coffee, ginger and pineapple, but it is also a driver of deforestation. Its governance platform seeks to balance production with landscape conservation and restoration.

Research in the Los Altos de Guatemala Model Forest

The research revealed patterns common to all three WBs that perpetuate gender inequality in the different family and social spheres. Despite efforts to build participatory landscape governance, machista patterns of thinking and the imposition of traditional gender roles continue to limit women's participation in decision-making in all three sites, as well as their access to paid employment and opportunities for empowerment. As in many other territories in the region, the disproportionate assignment of domestic and care-giving tasks overburdens women and restricts their presence in community and leadership spaces.

Testimonies collected by the researchers reveal that in these landscapes women face multiple "invisible barriers" that sabotage their participation, even when they manage to be present in meeting spaces. In Los Altos, for example, women frequently experience not being heard in community meetings and their access to decision-making positions is minimal. In Apurímac-Abancay, a generalized refusal to accept the existence of gender inequality was observed, which only hinders the implementation of possible strategies for change, while in Pichanaki, the overload of domestic work and limited access to economic opportunities places women in a position of undervaluation before the rest of society. These invisible barriers are compounded by gender violence, a social scourge that aggravates the situation of women, manifesting itself in forms ranging from labor discrimination to physical violence, with few effective policies to address the problem.

Another key factor exacerbating inequality between men and women is the formal and informal norms of access to land and economic-productive resources. In Apurímac-Abancay, inheritance and property norms favor men, limiting women's economic security. In Pichanaki, labor supply in agriculture is directed almost exclusively to men, while in Los Altos, the lack of financing and specialized livelihood support programs prevents women from achieving economic autonomy.

Education and access to key skills also represent a challenge for women in these landscapes. Girls and young women face obstacles in accessing sufficient technical and educational programs to secure economic and leadership opportunities. In Apurímac-Abancay, girls' education at the community level is still seen as secondary to that of boys, and in Pichanaki, young women have few opportunities for training in the agricultural sector. In Los Altos, the lack of intercultural bilingual education generates a disconnection with identity and belonging.indigenous and community These barriers not only affect women's personal development, but also limit their ability to influence natural resource management.

Another fundamental aspect of the struggle for gender equity in Model Forests, and one that requires greater attention, is the recognition of women's organizations on an equal footing. In Los Altos, for example, the Maya Women's Network Mam has played a crucial role in promoting women's leadership in the quest to revitalize the identity of indigenous peoples, although formal governance structures in this MF still fail to convene it appropriately. In Apurimac-Abancay, many women are involved in community development programs and water resource management, but their influence in decision-making is still limited to specific spaces. In Pichanaki, women have begun to organize themselves into networks to access training and improve their economic opportunities, although they still need to overcome structural challenges to consolidate their participation in formal governance spaces.

Policy enabling conditions are also a critical aspect. In many of these territories, the implementation of gender equity regulations is weak or non-existent. In Los Altos, although there are laws that promote women's participation in electoral and decision-making processes, their application is deficient, while in Apurímac-Abancay, it was observed that the lack of training in gender equality among public officials limits the implementation of effective policies. Creating more inclusive policies and ensuring their implementation are essential to achieve greater equity in the governance of these territories.

Finally, research found that gender inequality is compounded by the intersection of other factors such as ethnicity, geographic location (urban or rural) and age. The intersection between gender and ethnicity creates unique challenges for indigenous women, who often face discrimination and marginalization based on both their gender and ethnicity and, despite their fundamental role in the conservation of natural resources and the transmission of ancestral knowledge, their participation in decision-making remains limited and their contributions minimized.

In particular, the research highlighted that the differences between urban and rural areas deepen inequalities in access to opportunities, participation in governance and recognition of women's work. In all three territories, rural women face greater barriers than their urban counterparts, which limits their autonomy and reinforces structural inequalities.

The intersection between gender and age creates specific challenges for young women, who face additional barriers to participation and leadership, even though their involvement is key to the sustainability of natural resources, as they bring new perspectives and innovative proposals for land management. While each Model Forest presents particularities, there are common patterns that reveal how youth and gender interact to create additional barriers for young women, resulting in double discrimination.

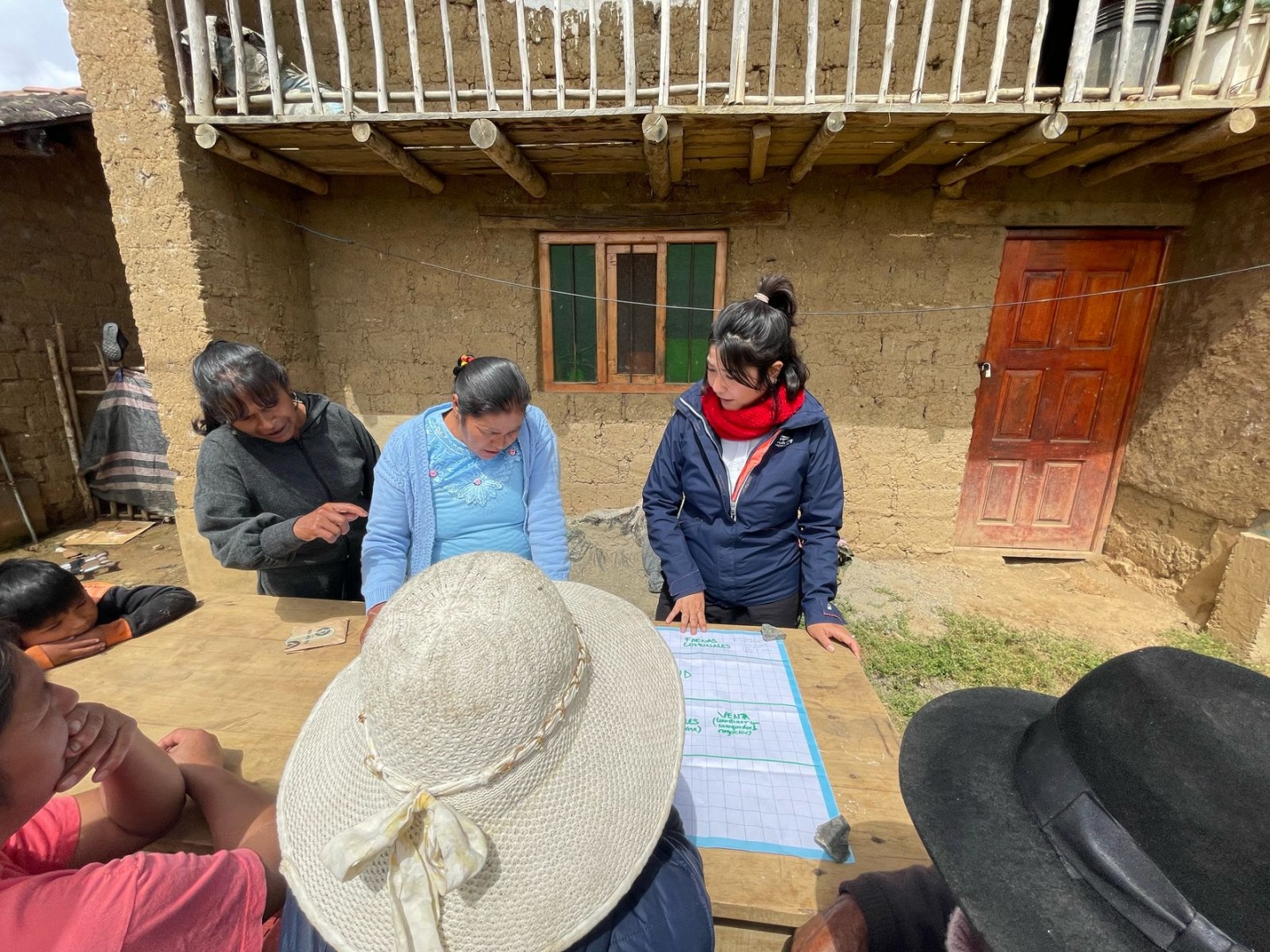

Model Forest Research Abancay - Apurimac, Peru

Recent actions, results and recommendations from Model Forests

Gender equity in Model Forests requires not only awareness raising, but also a profound transformation of the social and cultural norms that perpetuate inequality. In recent years, these MFs have implemented various actions to promote gender equity, albeit with varying degrees of success. In Los Altos, the issue has been integrated into the Strategic Plan, and although its implementation is weak, women are having an increasing impact in informal spaces. In Pichanaki, intergenerational dialogue spaces have recently been created, although a clear gender focus is still needed for these spaces. In Abancay, the need for a gender approach is recognized and there are key actors who have promoted training, although it is still urgent and necessary to promote women's leadership in territorial management.

Despite these intentions, it is still necessary to address the structural causes already identified. Across the three territories (and possibly throughout Latin America), it is urgent to work at the individual, family and community levels to reduce women's unpaid work overload, increase their access to resources and ensure an environment free of violence. With respect to landscape governance spaces, beyond their mere presence, women must have a voice and power in decision-making, as well as recognition of their forms of organization and traditional knowledge in the management of natural resources.

Transitioning from symbolic integration to effective participation and real impact of women in governance involves in many cases valuing cultural and knowledge diversity, especially in those territories where indigenous groups are present. In addition, both formal and informal spaces where women exercise leadership must be strengthened and valued, ensuring recognition of their contributions within decision-making structures.

Strengthening women's strategic capacities is always a priority, in which each model forest needs to identify its particular needs. In general, it is recommended that aspects be consideredsocio-cultural and site-specific , such as providing education in the mother tongue, holding workshops on economic, productive and labor rights, addressing gender-based violence where necessary, and promoting women's leadership programs.

Integrating gender equity into landscape management strategies necessarily entails adapting production, conservation and restoration approaches to make them inclusive and attractive to women and young people. On this path, it is necessary to generate spaces for intergenerational dialogue and it is key to promote alliances with educational institutions that encourage training in natural resource management.

Finally, the research concluded that, in order to promote the representation of women in decision-making spaces, it is also necessary to open spaces for reflection on masculinities and power dynamics within the communities and territories, since otherwise the totality of situations that limit the effective participation of women and the construction of fairer and more sustainable territories will not be addressed.

Key sources:

- Strategic Plan of the Latin American Model Forest Network (RLABM, 2023)

- Gender Strategy of the Latin American Model Forest Network (Torrez Ruiz, 2017).

- Systematization of the contribution of Model Forests to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (Ruiz-Guevara, et al; 2022).

- Youth in forest landscape restoration initiatives in the Pichanaki Model Forest, Peru (Bashi Pizarro, et al; 2024).

- Incidence of women in the governance of the Apurimac-Abancay Model Forest, Peru (Minato et al; in publication).

- Advocacy and participation of rural indigenous women in the territorial governance of the Los Altos Model Forest in Guatemala (Fueres-Guitarra et al; in preparation).